How Much Do You Have to Allege to Get Your Patent Infringement Claim Into Court?

Answer: Not much, at least for direct infringement.

In order for a patent holder to prove patent infringement, it must demonstrate that an accused infringer supplies a product or performs a method that comprises each limitation of at least one claim of a patent. Many times, a patent holder may suspect that infringement is occurring, yet lack the evidence to prove it. The discovery process is intended to provide patentees with the means to obtain evidence to prove their case. However, case law makes clear that one cannot simply file a lawsuit in the hopes of uncovering infringement. All of this begs the question: How much do you have to allege to sue for infringement? Do you have to allege details that you might only learn though discovery?

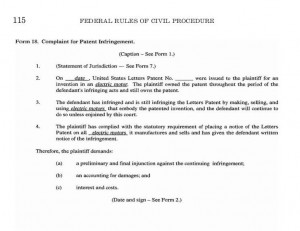

Historically, patent infringement complaints have required very little in the way of specificity. It has generally been sufficient for a plaintiff to allege that it owns the patent and that the defendant is making, selling, or using a product that infringes it. Plaintiffs have not been required to allege other details such as the particular claims that are infringed, the specific trade names of the infringing products, or to explain how the limitations of the patent claims correspond to individual features of the accused product. This has been perplexing for many accused infringers because it allows a patent holder to get into court without providing much substantiation of the basis of its infringement suit.

Then came Iqbal and Twombly. These two Supreme Court cases addressed the standards for pleadings in federal civil cases. They rejected the notion that a plaintiff could simply plead “legal conclusions” and required that pleadings state sufficient facts to draw the inference that the plaintiff had a viable legal claim. This led many to suspect that the patent holders would now be required to allege much more to avoid the dismissal of their complaints at the pleading stage. The Federal Circuit Court of Appeals has confirmed that such is not the case.

On June 7, 2012, the Federal Circuit issued its opinion in In Re Bill of Lading Transmission and Processing Systems Patent Litigation, ____ F.3d.___ (Fed. Cir. 2012) (Case Nos. 2010-1493, -1494, -1495, -1496, 2011-1101, -1102). In its opinion, the Court held that patent holders need only allege that the “defendant has been infringing the patent by making, selling and using [the accused product] embodying the patent.” There is no requirement to identify the claims that are infringed or even the specific accused product, much less to identify the manner in which the accused product features correspond to the claims.

The Court held that Iqbal and Twombly do not govern allegations of direct patent infringement. Instead, it is sufficient to plead patent infringement in the manner specified by Form 18 in the Appendix to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The Court held that Rule 84 of the Federal Rules expressly deems Form 18 to be sufficient and that the Rule cannot be trumped by the Supreme Court, but rather, only by Congress. Notably, the Court held that claims of indirect patent infringement are governed by Iqbal and Twombly because there is no form in the Federal Rules that describes the requirements for pleading these causes of action. Indirect infringement includes “contributory infringement” and “active inducement of infringement.” Contributory infringement occurs, for example, when someone supplies a component that has no substantial non-infringing use to those who use it to infringe with knowledge that the component is especially made or adapted to be used in an infringing manner. Active inducement of infringement occurs when someone takes steps to cause another to infringe a patent with the intent that they do so. To adequately plead either type of indirect infringement, patent holders must plead that a third party (usually the defendant’s customer(s)) is directly infringing the patent. For contributory infringement, sufficient facts must be alleged to draw the inference that the component supplied by the defendant has no substantial non-infringing use. For active inducement of infringement, sufficient facts must be alleged to infer that the defendant intended for it customer to infringe the patent and knew that its acts constituted infringement. For such claims of indirect infringement, it is not enough to simply allege the ultimate legal conclusion that a product has no substantial non-infringing uses or that a defendant intended to induce patent infringement. However, because of Form 18, at least for now, conclusory allegations of direct patent infringement are sufficient to prevent dismissal of a complaint.

In Re Bill of Lading does not provide patent holders with unfettered discretion to file lawsuits without a basis. Rule 11 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure has been interpreted by the courts to require a pre-filing infringement analysis before filing a lawsuit. However, Rule 11 and the pleading standards work together to deter baseless lawsuits. The more a plaintiff is required to allege, the more likely it is to be confronted by the Rule 11 requirements that any contentions of law or fact have support. In addition, courts may be disinclined to hear Rule 11 challenges until after some discovery is conducted. Thus, it does not provide strong protection against those who sue for patent infringement without a sufficient basis for believing that infringement is occurring.